I Owned a Skateboard Shop in 1987.

The History of AGGRESSION SKATES.

by Dave Larson

At 16 years old, I was a skateboard fanatic. I could think of little else. Girls, music, a driver’s license: these were all concerns, but each took a back seat to my obsession with that rolling balance plank. I wanted skating in my life at every possible moment. I devoured skateboarding magazines, covering every inch of wall space in my room with photos of pros doing the tricks I hoped to one day master. Scribbled pictures of skateboard logos adorned most of my possessions. I did everything possible to eat, drink, and sleep skateboarding. I developed an odd habit when riding in a car of watching the passing landscape and imagining myself skating it all. Carving the hills. Sliding the guard rails. Launching over the buildings. It was stupid. Childlike fantasy-level stuff. I still do it to this day.

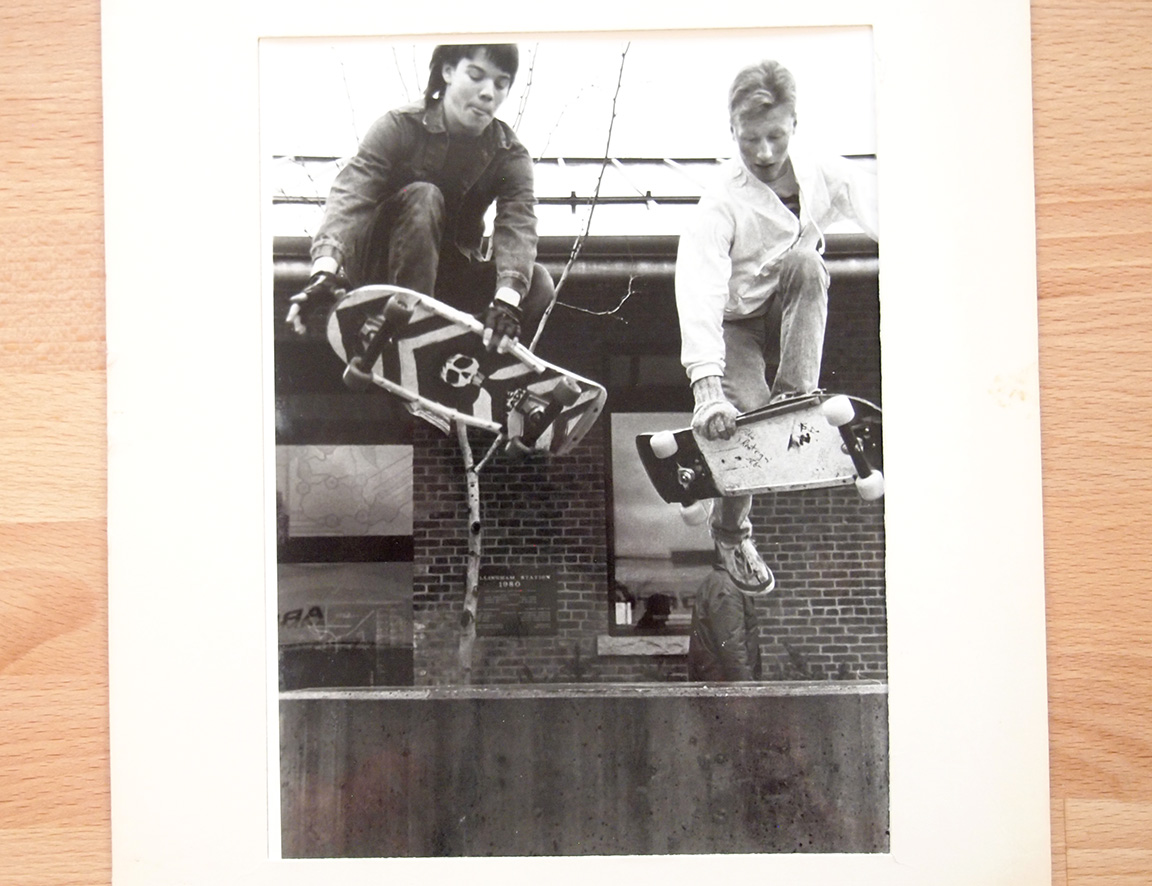

I got my first real skate set up, a Madrid John Lucero deck with Independent trucks, purple Kryptonics 85A wheels, and a complete set of plastic protective guards for Christmas of 1985. It was all I asked for that year, as did many of my close friends, and we entered 1986 prepared to shred our small town of Bellingham, WA to the core. By summer, we discarded the plastic guards in favor of having lighter, more responsive boards. They took more damage, but you couldn’t master the ollie with a tail guard, or live down the increasing levels of scrutiny and ridicule from other skaters for using nose guards, lappers, and copers. The pros didn’t use that stuff, so why should we? Of course, those guys got their rides for free, and when our stuff got trashed faster without plastics, it meant we had to buy even more of their signature gear. I understand that now, but I still stand by the idea we needed to shed the excess to achieve higher levels.

An acceptable set up included a deck with grip tape, trucks with riser pads, wheels, bearings, and plastic side rails. All from pro-level manufactures. And that last part was important. You needed the good gear. Most people either washed out of skating or rose to a level that demanded high quality equipment. The cheap toy store alternatives could not handle our increasingly damaging paces. Higher ollies, board slides, bomb drops, aerial moves off homemade launch ramps, seeing every surface as a challenge to master: this was our reality. A department store toy wouldn’t last a day of hard shredding. Even the high-end stuff succumbed to our abuse before long. We bought tons of replacement gear, and that fact led my friend’s father to say something that changed the game for us completely.

We’ll get to that soon.

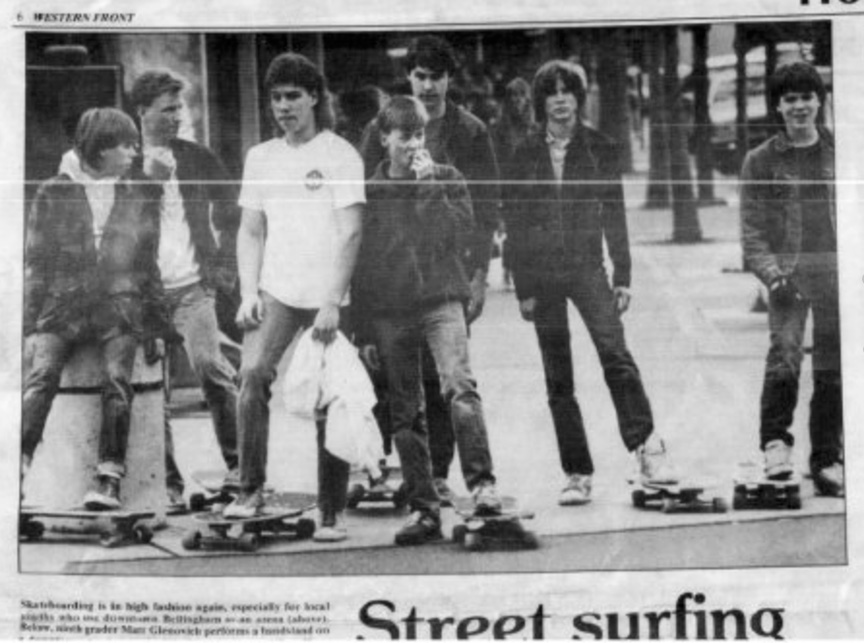

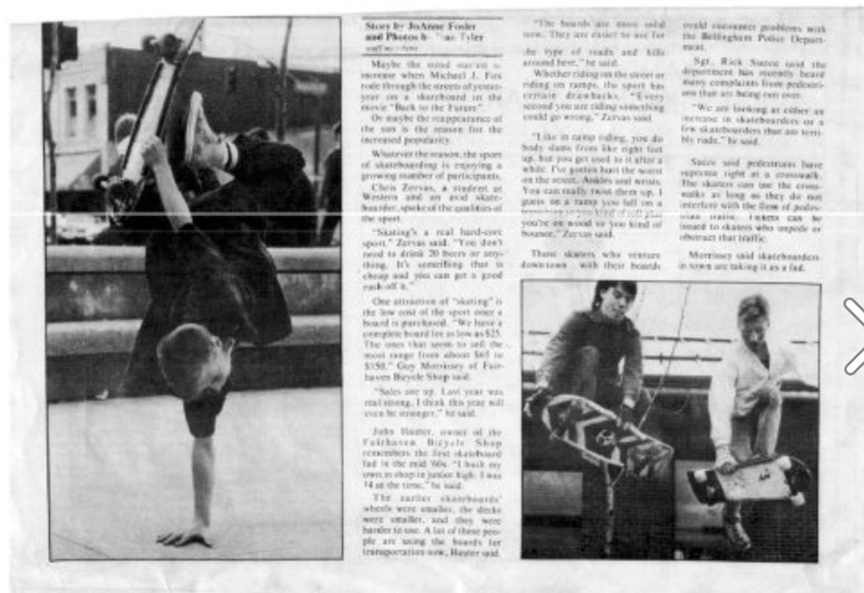

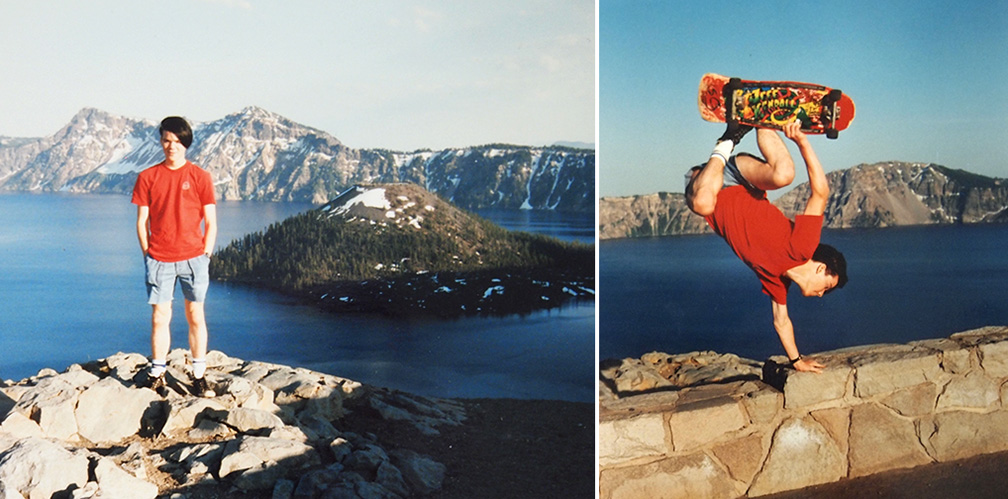

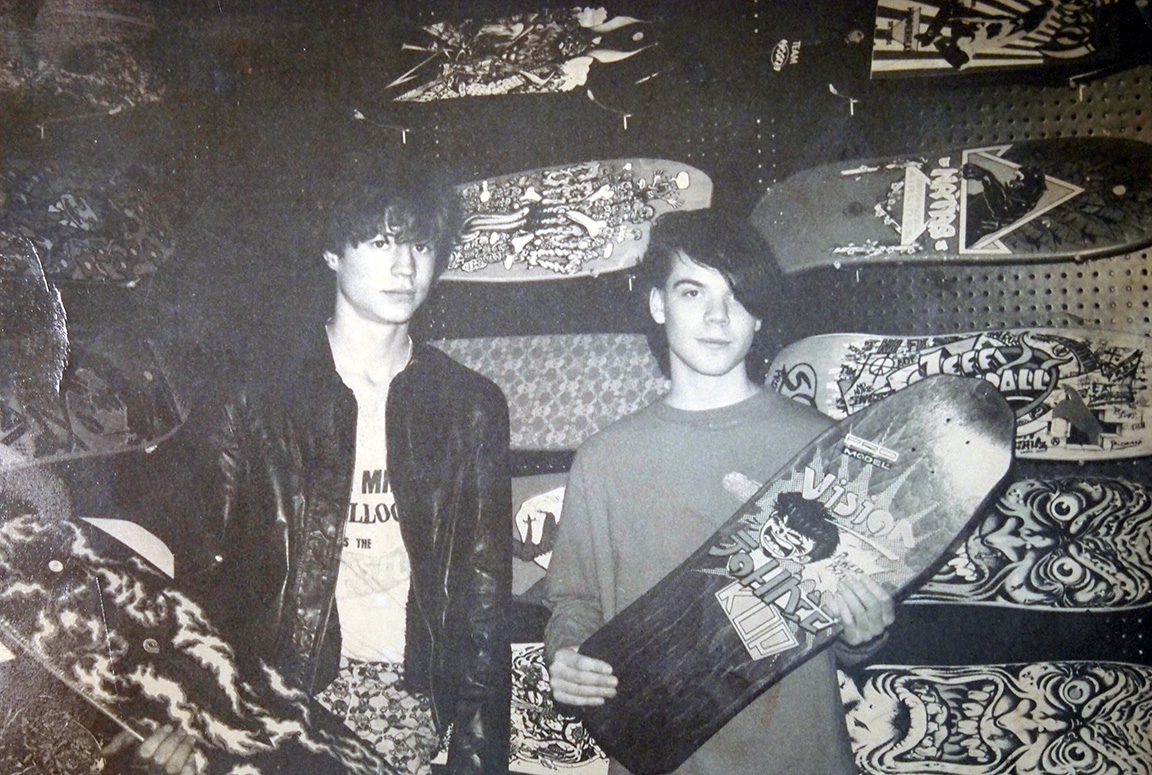

Some of us ended up in the college newspaper.

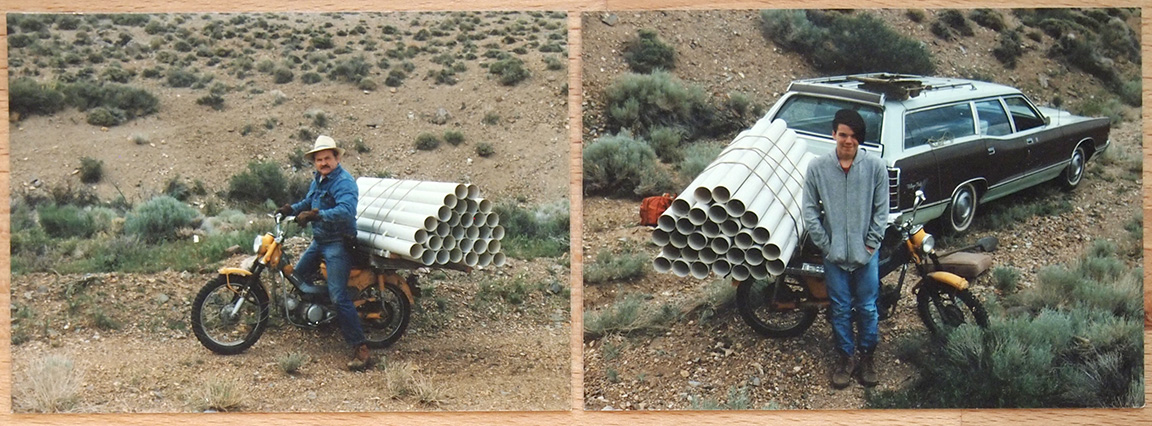

Going into the summer of 1987, I had only a vague idea of what might be ahead of me. I knew it definitely would include a lot of skating, hopefully a lot of time spent with my girlfriend, probably a fair amount of drinking, and unfortunately a summer job of some sort. Most of this got put on hold by a surprise offer from my father. He had a job staking mining claims in a remote part of Nevada and he needed an assistant. It would take just over one week, including the drive, and I would make $400. As sad as it might sound, I had never possessed that much money at one time before, and the idea I could make it in just four days and two long car rides was exciting. I jumped at the offer.

Photos from the Nevada trip

My father details much of what happened on this trip in his book, Gold Prospecting: The Ultimate Adventure. I won’t cover much of the same ground here other than to say it was some of the hardest and most dangerous work I’ve ever done. I earned that money. But I think the most valuable thing about the trip was the time spent with my dad. His son had gone through a lot of changes in the couple of years prior, and it must have been hard to get his head around how his kid went from showing some skill on the wrestling team and wanting to play football to flying around on a skateboard with weirdo hair and wearing anything he could get his hands on with a skull on it. To his credit, he was cool about it most of the time. There was pretty much ever only one real blowout over it, not worth mentioning other than to say it almost felt like this trip was a test of sorts. How would we be dealing with each other over the crucial next couple of years before I left home? As it turned out, I didn’t have to worry about that at all. I felt we really connected on this trip. We had great conversations, and I learned a lot about his world and his views, and vice versa. On the way back home, we had an opportunity to stop at a street skateboarding competition in Oregon called WILLAMETTE DAMMIT! and watch pro skaters tear it up in a parking lot. Dad took photos and seemed to enjoy himself. Here is how he described it in his book:

“It is hard to believe what those men were able to do with a board with four little wheels under it. I didn’t go there expecting to be impressed but I was. Let me tell you about my favorite: the rail grind. There was a steel rail about a foot high and about twenty feet long. The participant approaches one end of the rail with all the speed he can muster. Upon reaching the rail he jumps his board into the air, landing on the rail with the board crossways. The reason for getting up as much speed as he can is because to complete the rail grind, he must exit the other end of the rail with enough speed to continue skating. I imagined how many painful crashes these men had taken before perfecting this part of the competition.”

After the competition, the usual autograph panic and merchandise toss started up, but I wasn’t interested. I had my board, and I wanted to skate out on the street course. I wasn’t alone in this as many of the pros were still skating as well. My father walked around and took photos of the chaos while I skated with a bunch of the Alva team guys and got snarled at by Vision skater “Jinx”, who it turns out wasn’t nearly as cool as his pro model.

Click here for actual video from the competition.

After this event, everything was different. Whatever trepidation my father had about my chosen lifestyle seemed to evaporate, and I believe that came to be a key component in creating the skate shop later that summer. I had his support every step of the way.

Once I got home, the summer kicked into gear. Everything was about skateboarding, and my best friend Randy and I were essentially inseparable. Most nights I stayed over at his place, and we started drinking quite a bit, something I had done little of prior. As a summer for a 16-year-old could go, it was shaping up to be quite excellent. There was still the persistent problem of needing to find a job though, as school clothes, skateboards, and punk rock records were not going to buy themselves. That’s right around the time when Randy’s dad made his impactful observation about our skateboard obsession.

“With as much as you guys know about this stuff, you ought to open your own skateboard shop.”

…

Be careful what you say to a 16-year-old boy. He might take you seriously.

Randy and I kept coming back to the idea it might be possible we could open a skate shop. Sure, we were both 16, but we figured we could get around that if we could get our parents to co-sign on anything that would require it. The real questions we had were where would this shop be, where would we buy our inventory, and how much would it all cost? Money was an issue because we had none to speak of. I figured I could throw in my $400, but we were smart enough to know we needed more than that to kick it off.

Until that point, there had been two actual skate shops in Bellingham. Wipeout, which was a dark hole-in-the-wall with a sparse inventory, and a brand new, brightly lit place up the street from our high school called Season Surfer. Of the two, Wipeout was much cooler, but they never had much product for sale. These shops soon went out of business, forcing local skaters to buy skateboard gear from one of two bike shops: Jack’s Bicycles in town, and Fairhaven Cycle on the south side. These stores had a decent selection, but they overpriced it and were often out of touch with the skate scene. We would travel 90 miles to Seattle just to go to a real skate shop, so it made sense that Bellingham could use a place created by skaters for skaters. After we opened, the folks at Jack’s would take issue with this idea, but I’ll get to that in due time.

We skated over to look at the spot where Wipeout had been and found it still empty. This was not a surprise as it was run-down and not move-in ready. The location wasn’t especially ideal either. If I remember correctly, I was against us even considering this spot at first. The only thing it seemed to have going for it was the price, which we found out was under $200 per month, water/sewer/garbage included. We also tried to figure out how skateboard shops got their inventory. It wasn’t like we could just Google “skate shop distributors” because, you know, that didn’t exist yet. What we discovered were a few ads in Thrasher magazine we had never paid attention to before for skate gear distribution houses. We called those places and felt it out a little. Would they deal with us? Most said yes. One said yes, but they couldn’t sell us certain stuff as other people had that territory. After a bit of scheming we figured we could get everything we needed by dealing with three separate companies. We realized our store was possible. Now we just had to pitch it back to the man who started us down this road.

I don’t know what we had for dinner that night. Probably pizza. And RC Cola as that was a staple in the Clark household. As we were finishing up, Randy and I announced that we had something we wanted to talk to his dad & step-mom about. To their credit, they pretty much always took us seriously, and they were easy to communicate with, as parents go. They sat and listened to us lay out our case, starting with what his dad had said and then proposing our scheme. There was very little debate, they thought it was a good idea. Then came the catch: we figured we needed at least $1500 on top of my $400 to get started. Randy’s dad considered for a moment, and then said if we were serious and would actually do this legitimately, he would borrow the $1500 and loan it to us. And that was it. Just like that. We had $1900 and a crazy idea, and we were the kind of young and stupid that thought you didn’t need much else.

I have no memory of my parents reaction to this proposition. I just don’t remember telling them about it. To their credit, I can remember nothing but support coming my way from them on everything regarding the shop. Honestly, the entire middle of that summer is a blur in my memory. I know we made plans and scouted locations. We got a business license and opened a checking account, with Randy’s step-mom being an indispensable source of information on the proper way to keep records and such. But all the rest of the time we drank, and skated, went to Punk Rock shows, and hung out with our girlfriends. It was like some kind of last hurrah before responsibility set in. At least that’s how I looked at it.

One night, drunk (probably on tequila), I looked out the window at my car in Randy’s driveway and experienced the horrible realization that at some point in the future I was going to find myself behind the wheel under the influence. I was dead set against the idea, but I knew in that moment it would happen. Reaching in my pocket and feeling my car keys, I imagined different scenarios in which an emergency, an angry girlfriend, a forcefully pressuring peer, or any number of situations could break down my will when I was drunk. I swore to myself I would never let it happen. Then I drank some more.

People who know me now might find it hard to believe there was a time in my life when someone close to me expressed concern about my drinking. While we prepared to open the shop, my girlfriend Sherri did just that. I never had an actual problem, but she could see the frequency increasing and said something. It wasn’t a big fight or anything, and she might not remember even having that conversation with me, but it still hit pretty hard. The thing is, I never saw myself as that guy. I kind of hated the idea of partying and was only really comfortable drinking at Randy’s place. The closer we got to opening day, the more convinced I was that a change was in order.

After a search of other possible locations, we settled on the old Wipeout spot. There was just nothing else we could get into as cheaply and easily. The place was a wreck, just a large, empty room with a tiny back office space connected by a tiny hallway to a bathroom that looked like a set from a low-budget horror movie filmed where an actual horror had occurred. The whole thing needed serious painting and cleaning, and even after that all we had was a clean-ish open and empty space. My father came to our rescue by building up the inside of the store. He built us a sales/work counter and a wall of pegboard that turned the rear 3rd of the space into a large back room. We painted the pegboard black and got a bunch of metal pegs to hang product. It took shape quickly. Someone, I think it was Randy’s dad, found us two large counter-style display cases. They were either free or very cheap and didn’t look like much, but they were exactly what we needed to display all the smaller parts. We put them in an L shape out from the counter and this created our sales/work space in front of the pegboard. The only other item in front of the counters was a round, metal shirt rack, and I can’t remember at all where that thing came from.

I wish someone had possessed the presence of mind to take photographs of the building process, but this was a long time before the rise of digital photography. Pictures were expensive, and we had many other things to spend our cash on. Things like the product we were going to try to sell inside the store. We learned a lesson about ordering our stock very early on that summer: You aren’t always going to get what you order. We made our orders by phone, talking to sales reps that usually sounded pretty annoyed to be doing their job. The first order shipped to Randy’s house COD, and we eagerly awaited its arrival. When it arrived, it seemed too light to be everything we were expecting, and it was cheaper than we had planned for. Upon opening it, we discovered that many of the items we ordered were missing. This was a problem we would suffer with the entire time the store was in business. None of these distributors could tell you what would ship for certain. We might order 20 decks only to discover 12 of them had sold out before they pulled our order for packing. The flip side to this, we learned with some difficulty, was that if you over-ordered assuming some things would not come, every single thing would be in stock that week and you’d end up with a giant order you might not be able to afford. Throughout the course of our skate shop career this continued to be a problem, and at one point almost lost us control of the store. But as usual, I’m getting ahead of myself.

We made our first sale before the store was even open. Our friend Erin Marden came over to Randy’s house and bought some stuff, including one of the three decks we had. It was a Santa Cruz Claus Grabke with some clock-themed graphics. It felt so cool to see that gear go out with a smiling face, and that we had created a little extra money in the process wasn’t too bad either. We blew most of the money we had left on a larger merchandise order and begged the powers that be to let enough of it arrive to get us through our opening.

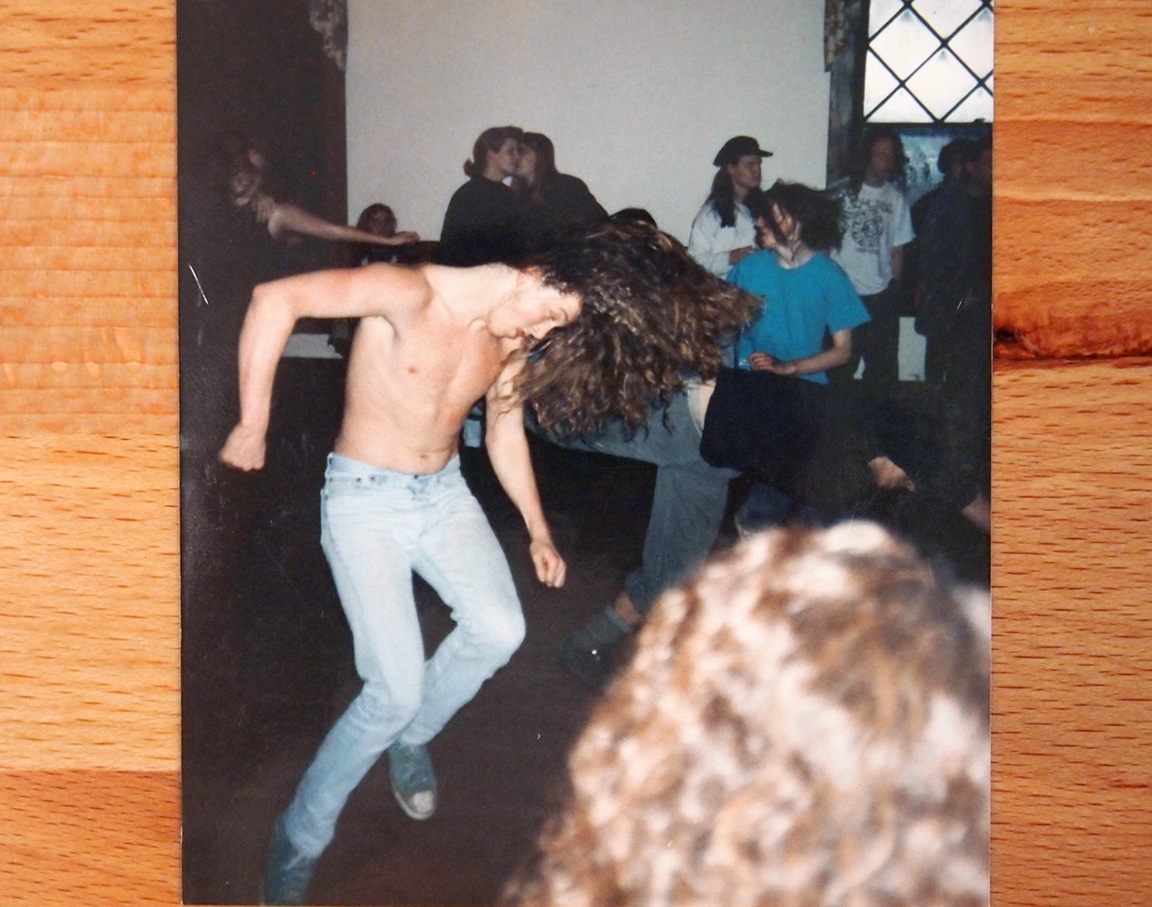

I don’t have a picture of Erin Marden from that day, but here is a photo of him moshing shirtless. It is an accurate enough representation of how we all felt.

The day was looming. We set Saturday, August 15 as opening day, and we had to hustle to have everything ready to go. My strongest memory from this time is painting the front of the shop while listening to music on cassette on Randy’s boom box. We had picked up “Some Great Reward” from DEPECHE MODE somewhere, and I completely fell in love with it while we worked. (Oh, you hate DEPECHE MODE? Here’s a challenge: go listen to “Somebody” and “It Doesn’t Matter” and try to say that with a straight face.) It is probably the association to new music that makes me remember this day so clearly. If I close my eyes, I can feel myself standing there with a paint brush in my hand, and the strange looks from some friends at the wimpy music we were listening to.

Once the front was ready, it was time to hang the sign. Our friend Joe Grady had drawn us a logo for the shop that we used on flyers to announce the opening. We asked him to paint this image in color on a 4×8 piece of plywood, and he came through admirably. It was a black background with AGGRESSION SKATES in graffiti-style lettering next to a cartoon skater doing a hand plant (a 1-armed handstand while holding the board to your feet with the other hand). I thought it looked incredible. We nailed it in place with one of us on a ladder holding it up, another of us working the hammer, and someone across the street yelling positioning instructions. I was sure it would end up crooked as hell, but when we stepped back to check our handiwork, it looked great. It looked like the front of a store. Our store.

We were nearly ready. Randy’s parents came through with a cash register from somewhere, and his step-mom ran us through a lesson on how to use it correctly so it would spit out a sales report on tape at the end of the day. (It worked pretty well for the first year.) All we needed now was for that final order to show up in time for the opening. I remember feeling stressed out that it wouldn’t arrive in time, but that might just be bleed over from the next two years of stress that I experienced. For the purpose of this story, let’s say that it showed up at the very possible last moment. I don’t know for sure if that was the case, but so many things in my life have worked that way that it may as well have been.

The night before we opened, I came to a serious personal decision. I decided that I was finished with drinking for good. I figured that if I was going to try to be responsible for this shop and prove to people that I was mature enough to handle it, I was going to need all the help I could get. In fact, after wrestling with the idea for many months, I decided that on our opening day I would “claim” Straight Edge. To explain as simply as possible, Straight Edge (abbreviated “SXE”) is a lifestyle of abstinence from drugs and alcohol that took root in fringes of the Hardcore Punk Rock scene in the early 1980s. If you’ve ever seen people at a concert or in a music video with a big black X marked on the back of their hand, that’s what that means. “Claiming” Straight Edge means that a person is stating their intention to follow that lifestyle FOREVER. That’s what I decided to do on August 15th of 1987 when I was 16 years old and working the very first day of my skateboard shop. As I write this, I am 44 years old, and it remains to this day, with one or two other possible contenders, the best decision I have made in my life. That is not what this story is about, however, so let’s get back to it.

I think we had 12 skateboard decks on opening day. Maybe. We had various amounts of the other things we needed as well. Probably enough to build up 6 or 7 complete skateboards. Most people didn’t buy complete boards though. Most of our customers were skaters who were buying various replacement pieces as needed. We didn’t even build up complete skateboards ahead of time as most preferred to choose their combination of components on the spot. If someone wanted a complete board, we would sell them all the parts to set it up themselves, or we would offer to set it up for them for free. I can’t tell you how many complete boards we put together over the years, but I think on that first day it was two. A lot of people came in that first day and we made decent money. I remember it felt like hard work and long hours although I realize now I had little to compare it to. Whatever it was, it was something new. We made it happen. Bellingham had a real skateboard shop again, run by two punk kids with nearly a clue between them.

The most important item we stocked and sold in the shop was the skateboard deck. Decks wore down and broke all the time, or sometimes you’d get tired of what you were riding, or a new advancement like a deeper concave or kick-tail angle would render your current board obsolete. Decks also served as the main visual component of the store with their colorful graphics and interesting shapes. The sometimes strange shapes were part of the fun back then. A few years later virtually all skateboards would have the same basic measurements. It was worked out to the Nth degree what single size and shape was optimal to best perform all the specific maneuvers needed to be an effective skater. Kind of like how the early Ultimate Fighting Championship matches winnowed down the world’s hand-to-hand combat techniques to the most effective combination of Thai kickboxing and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. It is without a doubt more effective, but it all really looks the same. These days, every fight is the same kind of tattoo’d douche-bro fighting another version of himself with essentially the same exact moves. In the early days of the UFC you’d have some fat, biker pit-fighter taking on an off-duty cop who was a black belt in karate, or a small man with a funny name destroying everybody from every discipline with his strange wrestling moves. It was fun. And so was deciding whether you preferred the Hosoi Hammerhead shape to the good old 10×30 pig, or if Alva’s tri-tail design was effective, or if H-Street’s new ultra concave made up for the fact that the decks themselves were of a slightly lower quality build. It was like having color before black and white, or maybe more on the nose, it was like having colored hair and Doc Martin boots in the years before Lollapalooza led to aging punks giving their toddlers Mohawk haircuts. Something like that, anyway.

For the rest of the summer of 1987, Aggression Skates was open from 10 AM to 6 PM, 7 days a week. Randy and I were the only workers, and at first we both wanted to be there all the time. This would change, of course, as the novelty of running the shop magically transformed itself into a daily grind, but for those first couple of weeks it was a dream come true. We had customers and were generally busy, but we didn’t make a lot of money. Every week we would decide what new stock we needed and could afford. We would call in the order on Monday and usually get the package on Thursday or Friday. People were coming in to see what new decks, wheels, stickers, and t-shirts had arrived that week. Opening those boxes was an exciting affair that never lost its luster. You had no control over what colors the items you ordered would come in. In some cases, you would order a pro skater’s deck only to discover that he had a new model out that you hadn’t seen before. Our distributers would tell us about the new items that had just come in, and much of that stuff we’d have to buy sight unseen. On the rare occasion you’d get something that was a stinker, but most all of it was just fantastic. I am biased on this issue, but I believe there have been few things in history as cool as mid-1980s skateboard gear. The design aesthetic, the colors, the function; it was a special and pure art. It was magic. Like incantations in a private language that opened portals to the secret playgrounds of the Earth. Skaters looked like colorful and evil freaks who committed dangerous and daring acts on improbable equipment. And I got to be a part of that every day.

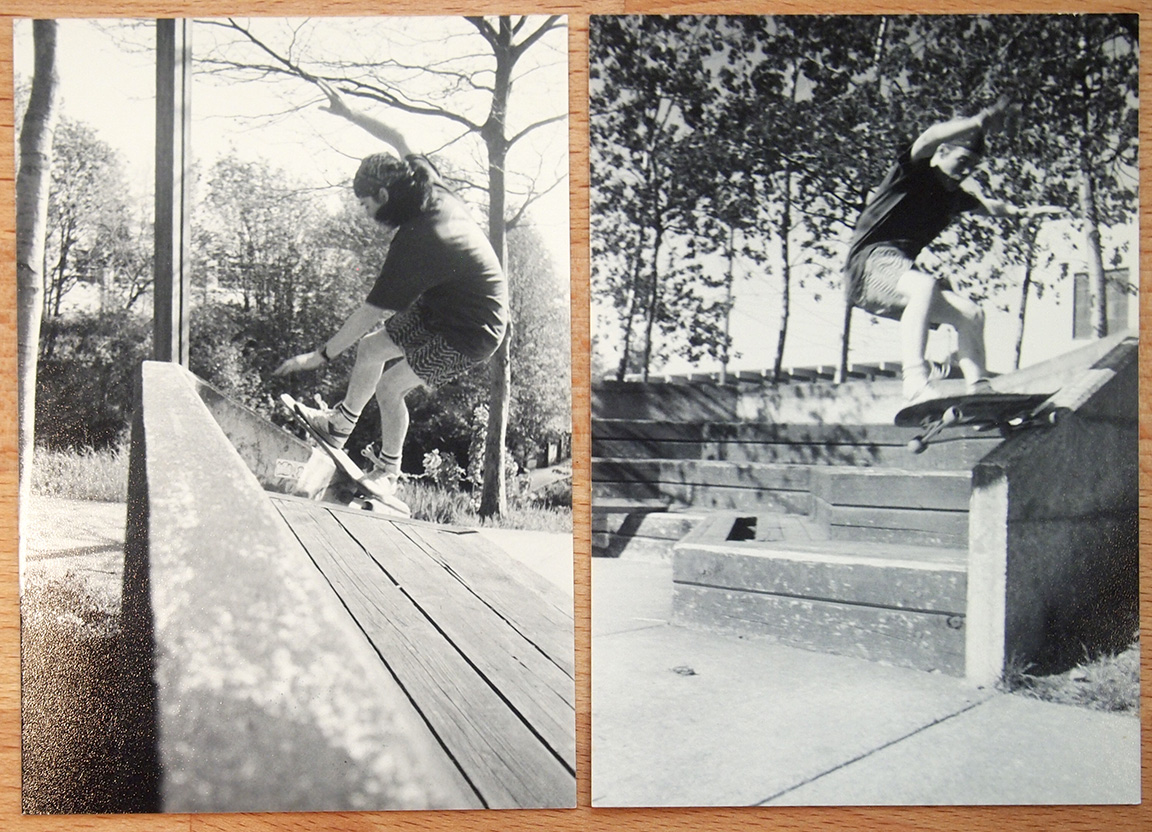

Dave skating the fish hatchery benches a few blocks down from the shop.

Randy and I entered the 11th grade as store-owning, skateboarding Punk Rockers. Plenty of people weren’t sure what to make of us. We were feeling pretty good though. We both had cars, steady girlfriends, and a dream job. What could go wrong? Nothing, at first.

We changed our hours to 3-6 PM weekdays and 10-6 weekends for the school year. We’d have a half hour after school to get to the shop and open up. It was a little easier for one of us to handle a three hour stint alone, so we switched off on the days we would work. Aggression was becoming a real hangout though, so we were often there on days off anyway. The main problem our weekday hours caused was a hinderance in our ability to receive our weekly orders. The UPS route that included our store often had the truck at our location before 3 PM. We’d get to the shop and discover a note saying that they had attempted delivery and would try again on the next delivery day. If it was Friday, that meant they’d try again on Monday, and that just would not do. Weekends without new stock were a waste of everybody’s time. A common Friday evening would include one of us heading out to the UPS facility and waiting for the truck with our package to arrive. After an initial annoyance at our insistence that we must have that delivery TONIGHT, the staff became used to us and were usually very cool about getting us our stuff. That’s how I remember it, anyway. I know for a fact that I spent long hours waiting at a remote facility with my financial life on the line, and I know that I almost never came away empty handed. But what I remember most fondly about these otherwise tedious trips, was a little thing we liked to call “off-road stylin.” There was a dirt road through a large, overgrown field that could be used as a shortcut to get to the UPS facility. Once we figured this out, we used it all the time. And once we found ourselves on that dirt, we drove like jerk maniacs. If I could have caught air off anything on that short stretch, I would have. I would have painted a damn flag on my roof and made my girlfriend call me Duke. I heard many screams of protest from unsuspecting passengers as the transition from pavement to dirt transformed me into some wannabe Baja racer. It was irresponsible, and it should have led to some terrible crash or breakdown. It didn’t though. I learned no lesson from my antics other than sometimes fun is fun and you get away with it.

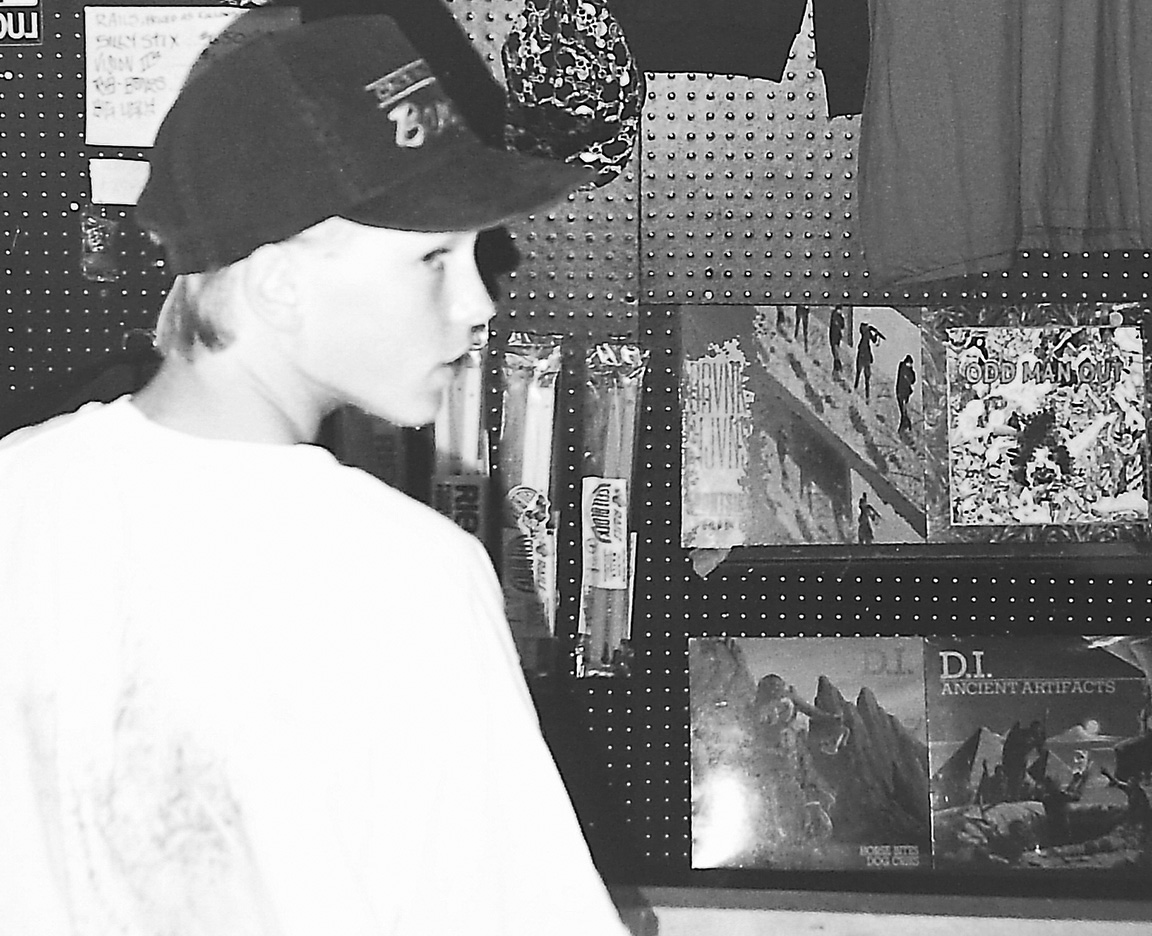

Various shots of the inside of the shop.

People came in on Saturdays more than any other day. On nearly every Saturday for two years, our shop had walls covered with new decks, cases full of new wheels, trucks, rails, and stickers, and a rack hanging with new shirts. It was usual for us to pull in somewhere between $400-$800 on a good Saturday. There was a little money in what we were doing, and people started to take notice. One thing that we worried about was theft. We never left any large amount of money in the shop, but there was plenty skate gear to make off with. The building was falling apart, and the two doors that led into our space could have been forced open with a strong shoulder. One day a young kid told me that he knew how to break into our store. I thought he was joking, but when he described the process I realized that he was right. If a person could get into any other part of the building, which was easy, there were access points in the ceilings to a crawlspace between the first and second floors. Get in, crawl across to our space, open the access to our back room, and you were in. The way this kid described it, I think he must have tried it for himself. All of this worried us, and our solution came once again from my father’s construction skills. He built us a large, heavy wood beam cage with a swinging door in the back room. This cage had wire fencing around it and the door was secured by a heavy chain with a padlock. Each night we took our most valuable stock and locked it in the cage. It was a little paranoid, yes, but all I know for sure is I have no theft stories to tell you. We really had few problems. Other than in a couple of instances I’ll get into momentarily, we were our own worst enemies.

From the very beginning, I was a problem. I understand this now. I understood it then, but there was nothing I could really do about it. You see, I wanted there to be rules in the shop. Just a couple, but I wanted them followed. My two big issue rules were “no one but Randy and I behind the counter” and “no skateboarding INSIDE the shop.” You’d think these would be easy to follow, but they most definitely were not.

Our friends wanted to come behind the counter. It’s not that they wanted to stand around like they were selling or helping or something, they wanted into the back room. We had a couch back there, and it made for a decent hangout. Sometimes when I couldn’t keep a lid on it, or when I just wasn’t in the store, there might be 3 or 4 skaters back there just hanging out. Now, you might be asking yourself why I would let this bother me. These were my friends, right? Well, yes. And there was nothing that really bothered me about it other than the fact that nobody would keep their mouths shut when they were back there. The store was a small space, and sound carried. Once you were in the back room, it was easy to forget that there could be customers just on the other side of the pegboard wall. Now, if these customers were other skaters, it didn’t matter. The real money came from parents though, and when they were in the store I didn’t want to hear a peep from the back. The type of language and conversation you would expect from 16-year-old boys would have been bad enough on its own, but we had one particular kind of slang that was in a special class. Someone, at some point, starting calling people “Jew” as a joke insult. I don’t know who, and I don’t know why. This didn’t sit well with some people, as you might expect, and before long it had morphed into “nazi Jew,” which seemed somehow better and worse at the same time. I am telling you this for context, and I know how horrible it sounds. To be clear, this wasn’t an insult that was hurled at the unknown passer-by or even at someone you legitimately had a problem with. This was specifically something to put on a friend. Example: your friend snaps you unexpectedly on the side of the neck with a rubber band. That would, at the time, possibly be answered with an outcry of “nazi Jew!” as you took a swing at them. Before long it had morphed into the final incarnation of “nazi Jew bastard” which seemed to contain the proper amount of syllables and disrespect to really get the point across. I tell you all of this so you will understand how it felt to be standing at the counter, halfway through the process of selling a nice, normal married couple a $125.00 skateboard for their impressionable 9-year-old, when from behind the wall comes a loud SNAP or SMACK followed by a scream of, “you fucking nazi Jew bastard!”

It happened more than once.

The other rule was “no skateboarding inside the shop.” Seriously. It’s not like there was even much room in that little place, but the space in front of the counters was just a painted wood floor. People would practice ollies, shove-its, and kick-flips – tricks that didn’t require moving around much – on that space and it drove me crazy. It scuffed up the floor and invariably someone would lose it and send their board smashing into a case or the wall which made the shop look beat up real quick. But we were skaters running a skateboard shop. Saying, “hey, no skating here” was about as uncool as you could be. The #1 offender of this was a guy we called “Pinhead” (often shortened to “Pinner”). A lot of other people knew him as Chris Vanderbrooke, who later moved to Seattle and played drums for the band ENGINE KID. (Years later I saw him get tackled by cops in Virginia Beach, but that is a very different story.) Chris had become a pretty good friend, and he hung out at the shop a lot. There were weeks when it would seem like he was there as long as we were. The only problem I had with it was that he spent most of that time rolling around in front of the counters and flipping his board around, customers or no. I’d tell him to stop and he’d just smile, say “dude, check this out,” and clack into some other trick. It was pointless. There was no winning on this one without alienating our skater customer base. It never got solved, either.

The lack of rules did not keep the shop from being a success. For a while, we did quite well. Well enough, in fact, to draw very negative attention from the fine folks at Jack’s Bicycles. One day a rather large fellow rode up to the front of our store on a bike. As he locked it to the railing outside, we had time to gather ourselves for the coming confrontation, as we knew exactly who he was. We had seen him working on bikes at Jack’s many times in the past as we perused their limited and expensive skateboard inventory. I remember it so clearly. The way he stepped inside the shop and removed his sunglasses in what I can only describe as an attempt to be menacing and dramatic. It kind of was, actually. He walked up to the counter and pointed at one of the Powell Peralta decks on the wall.

“How much for that Caballero?”

We told him the price. He looked around for a moment and asked about trucks or wheels or something. Then he lost it. I don’t remember it word for word. He told us that we couldn’t just come into town and undersell their store like this. Who the hell did we think we were? This wasn’t how competition was supposed to work. While he was going off, he was flexing, pressing his fists into the counter, leaning forward, and glaring right into our eyes. It was clear intimidation. Bear in mind, he was doing this to two teenage boys because their skateboard shop, that sold only skateboards, was a little cheaper than the bike shop he worked at that sold skateboards on the side. We didn’t back down and told him his bicycle store wasn’t our competition. We told him our product was properly priced when compared to actual skate shops and gave him examples. This only made him angrier. I don’t think he expected us to be able to talk back to him. He implied less than legal possibilities, and how would we like that? We told him we thought a bike store intimidating the teenaged entrepreneurs who had opened their own shop would make a great story for the local paper.

Have you ever looked into the eyes of someone who genuinely wanted you dead in that moment? I have.

He left, but said we would “rue the day” or something as he went. If you’ve never had the chance to watch as someone angrily unlocks a bicycle and then tries to storm off on it, I highly recommend it. Shortly after that the word got out that Jack’s would sell any skateboard deck at the wholesale cost as long as we were in business. While I can’t verify that this ever actually happened, I can tell you that shrewd skaters would sometimes bring it up when trying to negotiate a lower price on one of our decks. In the end, nothing really came of the whole thing. It felt good to stand up to that guy though. We felt like we had won something. We were beginning to feel impervious.

Oh, but did that idea get slapped away from us quickly. A far more powerful force than Jack’s thug bike mechanic was amassing against us. The storm of Randy’s parents.

It was all about bolts. Stupid little nuts and bolts almost sank us. I have mentioned that products were sometimes hard to acquire reliably. There was a brief but frustrating time when the nut & bolt combination used to secure the trucks to the deck of a skateboard became scarce. There was a specific-sized bolt with a special plastic-lined nut that was necessary to assemble a board correctly. If you didn’t have the right nut the vibration of rolling around would loosen things up. And they had to be strong for their size to not break immediately from the constant bashing and trashing. Imagine you rode your board off a loading dock or the rooftop of a low building. When you landed on top of the board, you would need it to stay together if you had any chance of rolling out of it and not killing yourself. Skaters would try various different combinations of what you could find at a regular hardware store, or what a dad might have lying around in the garage, but it was never good enough. You needed actual skate hardware. There were high quality nuts & bolts that we could order from distributors that handled this job nicely. Often though, even these bolts would break from repeated smashing. Somewhere around late 1987, the bolts started breaking at a higher rate. Either the manufacturing process had changed, or new tricks were putting different stresses on them. Some skate companies started making specialty bolt sets that were supposedly much better. They were also much more expensive. Most people still just wanted the standard stuff. In a very odd coincidence, the standard stuff suddenly became scarce. We would order hundreds and get none. We had to stop selling bolt sets by themselves just to make sure that we had enough to put complete boards together. It was frustrating, and it got much more so the day Randy’s dad was in the shop and heard us tell some skater we didn’t have any bolts to sell.

He was livid. Randy’s dad rarely got angry, but when he did, it could be a real sight to behold. He chastised us for being so irresponsible that we would not even have the basic items needed to run the shop. Now, he was not clued in to the trends and events in skating, and really had no idea about the issues regarding skate hardware that I described in the previous paragraph. All he knew in that moment was that we had failed him, and that our flustered explanations sounded like typical teenage excuses. You see, we were right at the point with the shop where we had taken the measly amount of cash we started with and reinvested everything so that the shop was well-stocked and starting to look really good. We weren’t even paying ourselves to work there. It was all for love and growth. What we hadn’t done yet was pay Randy’s dad back any of the cash he loaned us to get started. To be fair, there had never been a specific payment plan stated. The idea had always been to grow until there was money and then take care of it. We thought we were doing great. Unknown to us, the bolt issue was the last straw on the back of a camel we didn’t even know existed.

Within a day or two, we got a visit at the store by Randy’s dad and step-mom at closing time. They told us they were taking the shop away from us. We had screwed up and were not taking any of this seriously as we had not paid them any money back and did not even understand that we needed basic items in the store. From that point forward, they would handle everything and we would be their unpaid employees until they could turn things around. It was brutally crushing, and a scolding on a level we were definitely no longer used to. I looked around the store and saw all the work we had put in, all the stock we had built up, thought about all the hours doing every aspect of running that place we had both done, and realized I had to fight for it. Speaking with no idea what I would say ahead of time, I surprised the hell out of all of us. I told them, in the most respectful teenaged words I had, that if the point of the store was a life experience for us, then we needed to use this situation as something to learn on. That it would have value if we could use it to adjust our direction and understand what was working and what wasn’t. I told them we were well aware of the bolt situation and that Randy and I would seek out some remedy for it even if that meant just having an alternative available that we could get at the local hardware store for those times when there was nothing else to buy. I was pleading, but there was a confidence in it I don’t think they had seen from me before. And it had to be me. Randy was their son; probably too close to them to be heard clearly in this situation. I told them we had not paid them back yet as we had reinvested everything into the store, but now we understood the situation and could create a payment plan that wouldn’t hurt our growth and still get the money back to them within months. With pure sincerity, I asked them not to take our work from us and to trust us like they trusted us in the beginning. I said please.

From the looks on their faces, I don’t think they expected that. I hadn’t expected it – I hadn’t had time to expect anything – but it seemed like I might have gotten through to them. They didn’t even spend any time discussing it alone before telling us that they liked what they had heard, and if we could keep up our end of the bargain and get the money back to them, things could continue on as they had been. We agreed, and they left smiling. Randy and I breathed a sigh of relief. I think we would have rather gone up against roid-raged bike mechanics than his parents any day. We held up our end of the deal, paid them back in short order, and never heard another word about it.

One other thing we had to contend with was the fact that skaters were still essentially looked upon as criminals in polite society. However much praise we might have been getting for our entrepreneurial spirit, it was still undercut by the fact that many people just did not like our kind. There had been a skateboarding ban in the retail core of downtown Bellingham for about a year. The rules were that skateboards could not be ridden in what was essentially the 4-block by 5-block middle of downtown between the hours of 9 AM and 6 PM. The idea was that skateboards on the sidewalk were dangerous to shoppers. There were a couple of good skate spots down there, but for the most part this ban just made travel by skateboard annoying if you had to move through downtown. You either had to go around, or pick it up and walk through. The cops were quite serious to enforce this, and stories of skateboards getting confiscated, something not provided for in the law, started to circulate. We took the ban seriously. One thing that was pretty fun was meeting up with a bunch of friends after 6 and having a nighttime skate session in the mostly deserted downtown core. There was basically no one there to bother. We got by, complied with the ban, and there were no issues.

Then, for no reason at all, there was an issue. The city council proposed extending the skateboarding ban to 24 hours a day, based on no incident that anyone could point to. It was announced that they would vote on it at an upcoming meeting, and that they would hear public comments before the vote. Randy and I went to the meeting, along with a gaggle of skaters in support. It must have been an amusing sight. The council read the text of the proposed new ordinance and then allowed a couple of people in support of the extended ban to speak. This consisted of two elderly people who said that skateboards scared them and made it terrifying to walk on the sidewalks. They said they were afraid skaters were going to run into them and that we were a nuisance. What they did not say was anything thing about how extending the ban was going to help them, as these people were never out downtown after 6 PM, and they did not reveal that the examples they gave of prior encounters with skaters downtown were either from before the ban or with people who were in violation of the current law as it was. They were thanked for their comments and everyone acted like they had described a truly grave issue. Another point that was made, I believe by someone on the council, was that skateboarding was a dangerous activity and an insurance risk for the city.

A member of the council then said that he understood there were people from the opposing side who might like to speak. Randy and I came up to the podium and introduced ourselves as the owners of Aggression Skates. I don’t remember who of us said what, but between the two of us these basic points were made:

1. Nothing had occurred to make this ban extension necessary.

2. If there were issues regarding people ignoring the current ban they should be addressed by enforcement of the law as it stood.

3. This ban might actually negatively affect our business, as skateboarding already had enough negative perception.

4. Skateboards were also used as a form of travel, and having to take a longer route or walk, especially at night after getting off work, was cumbersome.

5. Skateboarding was no more dangerous than other things young people did for recreation, especially when compared to other, more accepted sports. There were no bans on football or bicycle riding, and insurance concerns were not something that rendered those activities into something that the council should ban. Since the safety of skaters had nothing to do with the issue at hand, it should not be considered.

I thought we did pretty well. We were in a completely uncharted territory, but kept our cool and communicated clearly and with respect. Not that it mattered. The same councilman who had brought up insurance, someone who’s name I haven’t deemed fit to remember, said that while he appreciated the fact that we had come to speak, the fact was that skateboarding was dangerous and a possible threat to the bright futures of the city’s children. I don’t remember any of what he said word for word, except for the following sentence which also appeared in the newspaper the following day: “You can’t be a brain surgeon if you’re brain dead.” Indeed. A member of the government said that to me, when I was trying to participate in the process, as a justification for extending a ban that was not intended to stop skateboarding as a whole but rather keep a shopping area clear for shoppers. But what a great line, right? In the end we made no difference and the extended ban passed.

The extended ban did not do anything to deter skateboarding in Bellingham outside of the small shopping district. What did start happening with alarming regularity was police telling skaters they could not skate in areas that were not included in the ban. Apparently the word had gone out to start cracking down because kids kept coming into our shop and telling us that cops had forced them to stop skating in places that should have been legal. When asked why, these officers would say there was a ban on skateboarding in Bellingham. This was of course not true and definitely was a threat to our business. Randy and I headed down to City Hall to clarify the exact text of the ordinance. A helpful clerk got us a copy of the law, complete with a highlighted map of the exact banned area. We thanked them profusely and headed to Kinko’s Copy Center to make a pile of duplicates. We handed these out to every skater that came into the shop for next couple of weeks so everyone would be on the same page with just exactly what was the law. I folded up a copy and put it in my wallet. And then before I knew it, I needed it.

A few of us were skating on the outskirts of the banned area one afternoon, about 1 block outside of it. A pair of Bellingham’s finest approached and told us all to get off our boards. I asked why and was told that there was a skateboarding ban in town and that if we didn’t stop skating, we would be ticketed and our boards would be confiscated. As I pulled out my wallet, I let the officer know we were aware of the ban and were outside the banned area. While I unfolded my copy of the ordinance, this fine public servant informed me that I didn’t tell him where the ban was, he would tell me. As I handed him the paper, complete with the map proving we were in the right, I said that I would not tell him, but this would. Remember when I asked if you have ever looked into the eyes of someone who genuinely wanted you dead in that moment? Well, has it ever been a cop? Before this now-seething monster could decide which sort of punishment he would dole out for my crime of being right, his much more reasonable partner put a hand on his arm and told him I was correct. He handed my paper back and guided his partner away, smartly avoiding the genuinely ugly scene I was preparing to make upon my arrest. Now, if anyone ever doubts the concept of white privilege, feel free to use this story, and the fact that I am still breathing today, as a clear example.

Shortly after this encounter and what I have to assume were other similar examples involving the skaters we had armed with the truth, the cops backed off and quit trying to pretend that we were breaking imaginary laws. At least that is how I remember it. I know that it never did get any worse.

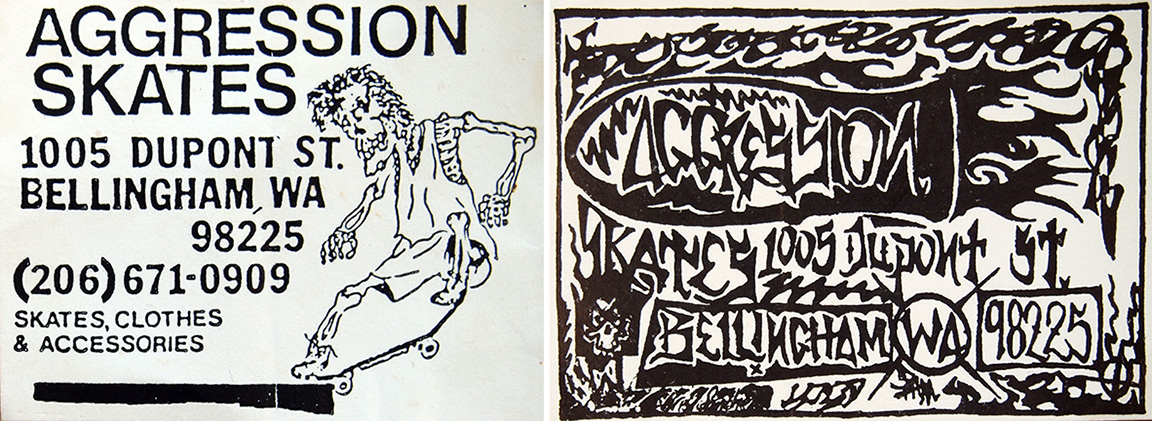

Examples of Aggression Skates stickers. Dave’s on the left, Chris’s on the right.

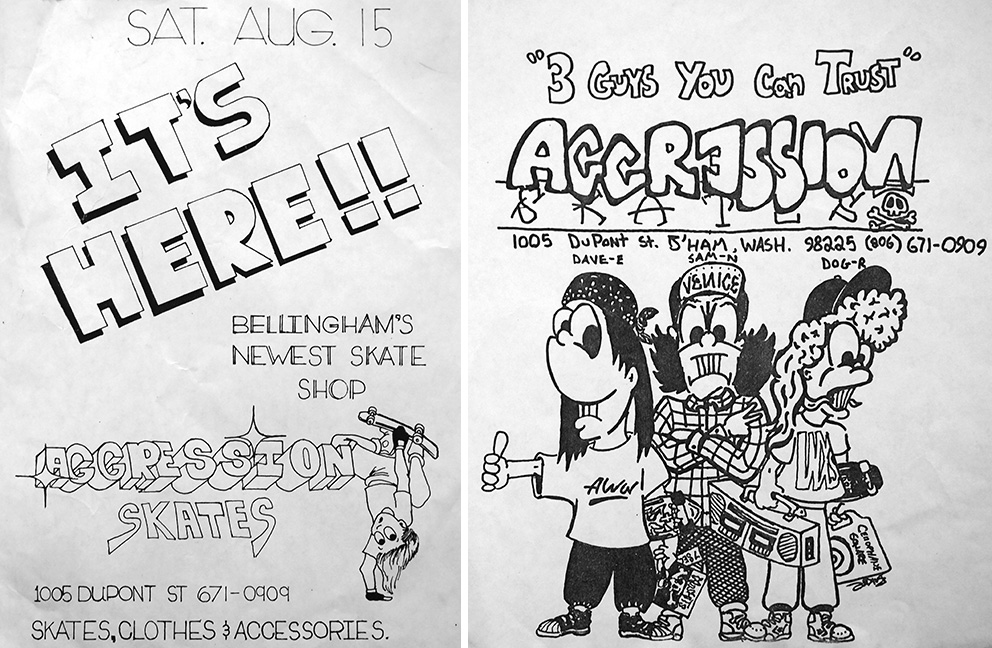

Aggression Flyers. Left side by Joe Grady. Right side by Bill Baker.

So we kept on selling skateboards and working and skating most every day. Eventually we started paying ourselves a little money every week. Not much, but something. It wasn’t long after that Randy and I decided that we should bring a third person in on the business as we were starting to get a little burnt out. Our friend Chris was the natural choice. In fact, had we intended to have a third person from the start, it would have in all likelihood been him. We cut Chris in on 20% of the shop in exchange for working 1-2 days a week. It seemed like a good deal, as it bought Randy and I extra time off and infused the shop with another point of view, which was not a bad thing. Chris made a number of sticker designs for us that were quite cool, despite my constant complaints that they were becoming increasingly difficult to read as the art became more chaotic. He worked his days and bought us time and it was all good. Regardless, in the end I felt bad that we brought Chris onboard. He had to ride with us on the downward side of things, and in a way it just added one more person to be disappointed as it all came to an end.

And come to an end it did.

The summer of 1989 was probably the lowest, saddest, most worthless period of my entire life. I was a wreck. I had graduated from high school and moved into my first place. With Randy, of course. I thought I could handle it, but it was too much change. Before I could adjust to my new reality, my girlfriend of 2 1/2 years dumped me. I had already stretched myself too thin, and I hadn’t left any space for pain. I was the kind of guy who actually believed that the things I put together in my teenage years were supposed to last forever. The kind of fool who believed that the suffering and joy we had experienced was a foundation for a future together rather than just training to call upon while trying other people on for size. Who puts stupid ideas like this in a teenager’s head? Idealistic? Yeah, well, welcome to the other side of the coin, dipshit. It’s funny how the world will wait until you’re low to drop heavier loads on you. She sat in my car in front of her house and she wouldn’t look me in the eye. As she got out, she wouldn’t kiss me goodbye, pretending to be distracted by something. It was all new behavior, and I knew damn well what it meant. One block from her house, the rage kicked in. I stomped the gas to the floor going through an intersection and something underneath the car gave out and died. It rolled to a stop, leaving me unable to flee the scene at speed. I left the car on the side of the road and walked home in a state of desperate sadness and fear. It was really kind of pure and glorious, but I lacked the perspective to appreciate it then.

I can’t even remember most of the summer past that. It’s blocked. Somewhere along the way it was decided that we couldn’t keep the store going and still make enough money at side jobs to be able to pay rent on our new living situation. We came up with some stupid idea that we would transform the shop into some kind of mail-order business and still sell stuff direct to people out of our rental house. It was a foolish idea, and it was never going to work, but I was too crushed to come up with anything else. I couldn’t see that we were destroying a foundation from which we actually could have risen to success. We had already started adding punk records to the selection in the shop. If we could have expanded that inventory, we might have been able to weather the downturn in the skate industry until Tony Hawk and the X Games brought it all screaming back to profitability and small towns everywhere, including Bellingham, started building new concrete skateparks. (Apparently in the end it didn’t matter if some of these future brain surgeons became brain dead, as long as there was enough money in it.) I couldn’t see it though. I couldn’t see anything. My ability to scheme was lost, and no flash of inspiration or intuition presented itself to save us. We closed Aggression Skates on August 15, 1989, exactly two years after we opened it.

I don’t know where our sign went.

Time has had its way with my memory. So many details are lost. I should have written all of this down as it happened. I should have saved all of our receipts, packing lists, and business records. We should have taken more pictures, and some video sure would have been nice. That is just not the way we thought back then. As it is, what you see and read in this article is all that I have left. At least, all that I am aware of. It amounts to very little. Sadly, that is the basic point of the story.

After the shop closed, I worked at Kentucky Fried Chicken. Life has many low points.

Shortly after that I started a record label called Excursion that I ran for over 20 years. That’s another very long story full of highs and lows of its own.

Another time, maybe.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Epilogue:

That girl who broke my heart? She became a fine woman and mother who I’m proud to call a friend to this day. She wasn’t the first one or the last one to rake me over the coals, she just happened to be the one in this story.

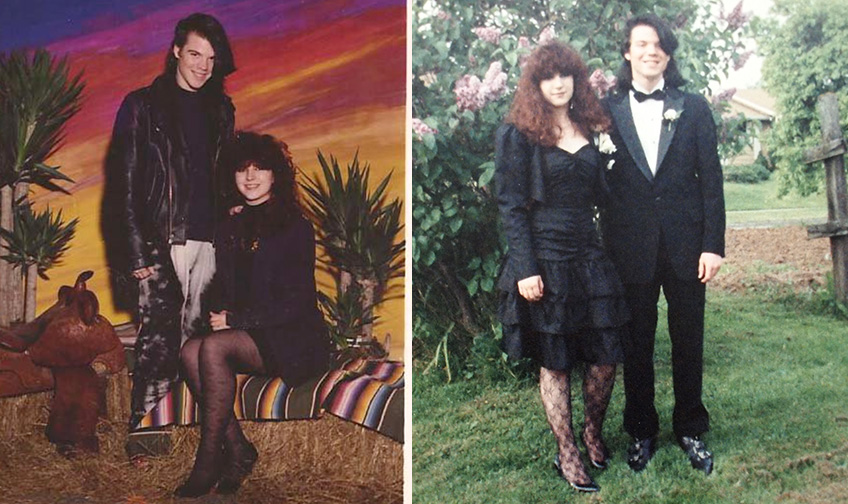

We did look cool though.

As for Randy and I, after a few more years of being roommates on and off, I moved to Seattle and he moved to Oregon and we lost touch. In those strange, lost days before everyone was online on social media, I feared that maybe we had lost touch for good. He eventually surfaced though, back in Bellingham again. Here’s a photo of us at Rob Eis’s Crucial Barbecue reunion a few years back:

And here’s a photo Rob snapped recently of the old store location:

NOBODY’S NOSE is created by Dave Larson.

Dave’s book SHADOW KILLER, a story set in the world of Hugh Howey’s book WOOL, can be found at Amazon for Kindle here:

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.